'Volume' is a Robin Hood origin story for modern gaming

"Honestly? Volume is my inner 12-year-old," gushes Mike Bithell one evening.

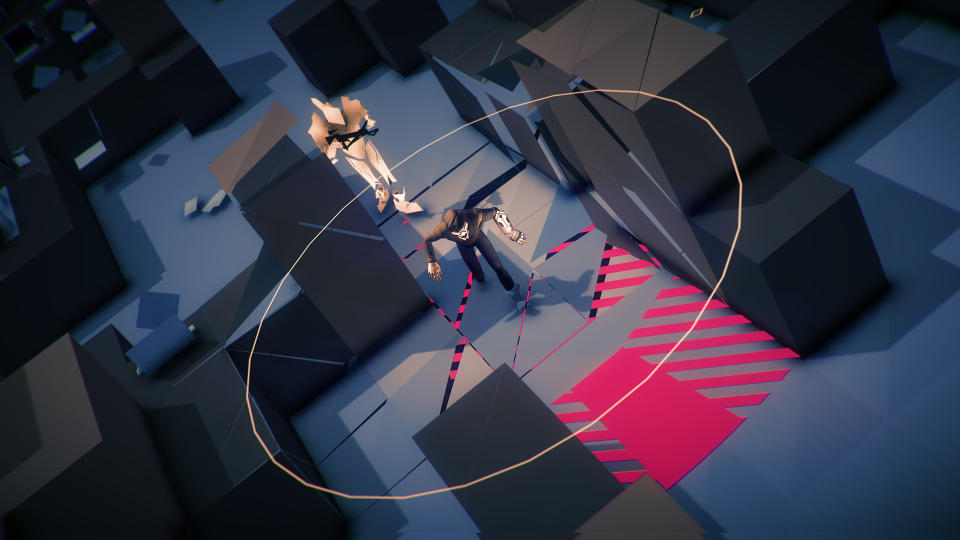

The game in question is a futuristic stealth-puzzler; a non-violent Metal Gear Solid played to the rhythms of Hotline Miami. Its protagonist is a man named Robert Locksley who, after stumbling over a military training program, decides to televise simulated robberies against Britain's most well-to-do -- an audacious move that soon garners the attention of a powerful enemy. If all this sounds a little familiar, it's because folklore had Robin Hood doing the same for 800 years already.

The British developer makes no secret of his affection for the benevolent outlaw. Volume is openly branded as a "near-future retelling" of the British folk hero's tale. Its protagonist is named after the brigand himself, while the antagonist and the game's sapient AI share a name with his romantic rival and minstrel respectively. The game even includes a modern-day version of the bugle that the bandit uses.

But, Volume isn't just about the Robin Hood mythos. The game draws inspiration from all the things a young Bithell loved. "I have so many memories of my dad sitting me down and going, 'Mike, you're going to watch Blade Runner. You're going to watch Predator.' I remember there was one point where he was like, 'Right, we're gonna watch all of the '80s action movies, because this is the thing you need to do.' And they just blew me away."

Chuckling, he confides: "A lot of the surface-level stuff in Volume is very much me as a teenage boy loving all of that stuff and kind of just making the game that I know I would have thought was cool when I was a teenager."

Bithell talks quickly and without reservation; a spill of eager ideas that parallels his approach to games. Thomas Was Alone -- his first title and a BAFTA Games Award winner -- surprised players with its juxtaposition of simple geometrical shapes, clever storytelling and engaging narration from British comedian Danny Wallace. Then, he raised a few eyebrows by opting to make Volume instead of a sequel.

Bithell comes across as a man with a clear sense of vision. Even the thought that goes into Volume's underlying motifs is evocative of that clarity. For example, Bithell believes the Robin Hood and steampunk aesthetics used in the game share more roots than most people think. They both represent a generation's longing for a conceptual ideal.

Where cyberpunk is "almost mid-century futurism" longing for a period that did not exist, steampunk, he says, was devised by people who yearned for weight and brass of the Victorian era despite being surrounded by clean, invisible technology.

"What's really, really interesting to me is that Victorians totally had steampunk. They called it romanticism. They basically were in a period where they're like, 'Oh, all these bloody factories and technologies moving on. Why can't it be like the old days when you had Knights of the Round Table and Robin Hood?' And all these kind of heroic medieval fantasies that they made up."

"Victorians totally had steampunk -- they called it romanticism."

Bithell believes the literary sentimentalities of the Victorian era helped shape the Robin Hood legend over the years, by stealing characters from different tales, changing details, and revising the outlaw's very nature -- all to make it more beautiful and romantic.

"I mean, he was never real, but the stories that were told early on were basically a guy who ran around the forest beheading people," laughs Bithell. "Not a friendly story."

This metamorphosis is, in part, what appeals to him as a game maker. "I'm basically doing an adaptation of the story that's been adapted for 800 years. To me, that's exciting."

While Bithell has hopes of exploring other aspects of the vast mythos, Volume is focused on the beginning -- the pivotal moment when the protagonist decides to become the everyman's hero. According to Bithell, the game spans the last three hours before Locksley is captured, and much of that time is used to explore the interplay of relationships between its characters.

The tautness of the narrative bellies the game's depth. Creating Volume is difficult, so much so that Bithell hired an entire level team to assist him. "It's daunting. Really daunting. Scary."

"With Thomas Was Alone, the matrix of relationships between things was really simple," he explains. "Like, every character has to jump high. Some have different abilities, but every puzzle was basically some twist on these things."

Volume, on the other hand, is a veritable smorgasbord of overlapping systems, comprised of everything from player abilities to environmental interactions to enemy behaviors. Bithell relates how his designers can send him a level, and he can respond with five different solutions, none of which would be the one originally devised, but would still feel "cool and creative," nonetheless. "I think it's a more open-ended approach to game design. It's not just like, 'Here is an idea I had; you have to try and come up with what's in my head.' It's more setting a scenario up that the player can have fun messing with."

While the internet seems unanimously excited about Volume or, at the very least, optimistic about what it has to offer, that wasn't always the case. Despite their popularity, stealth games can be a difficult sell. Especially if you're known for two-dimensional indie platformers.

"I struggled, yeah." chuckles Bithell. "Like mates were telling me, 'Don't go and try and do a big stealth game. Make a sequel! Make another game about rectangles! Make it about circles if you have to, but keep it on that level' And I was like, 'No! I want to make something awesome and big and massive!'"

Bithell held onto his optimism despite the affectionate objections and the heckling of strangers. He recounts an incident at Indiecade East when he first presented an extremely early prototype of Volume, which only allowed players to "place walls, make a level and run around as the character."

"I said, 'No, dude. Two years. Trust me. It's gonna be cool.'"

"A dude was, like, genuinely laughing at me at Indiecade," he recalls. "I didn't know who he was. Just a dude who was like, 'Oh, is that your game? Really, is that your game? You just made a room with some cubes in it. Well done.' And I said, 'No, dude. Two years. Trust me. It's gonna be cool.'"

But even if it isn't, Bithell still wants to carry on making games.

"If Volume comes out and sells two copies to, like, my mum and my girlfriend, that would obviously be horrible," he says. "But the way we've budgeted means that I get another go at it. Basically, we have enough money in the bank. We can make another game for a couple of years and see if that works instead. I've not bet the entire Thomas Was Alone money on this."

While it might sound otherwise, his caution isn't born from lack of faith in the game, but pragmatism. Bithell is quick to point out that no creative ever has a completely successful run. "Your favorite filmmaker, your favorite musician, your favorite ... whatever has all made some awful stuff," he says. "Everyone has flops. So, that's kind of why we planned for that, to an extent. We know that some of our games aren't going to be as well-received as others and we plan accordingly that we can soak that up."

That's all that really matters -- that we keep on making video games. Because it's the best thing ever."

"We've got an out," he stresses. "[If] it doesn't work, we'll be okay. We'll be able to keep making games. And that's all that really matters -- that we keep on making video games. Because it's the best thing ever."

Volume is due out August 18th on Steam, PlayStation 4 and Vita -- we'll also bring you our impressions of the game from E3.

[Image credits: Mike Bithell Games]