Pluto may have a 60 mile deep liquid water ocean

The excommunicated "planet" is full of surprises.

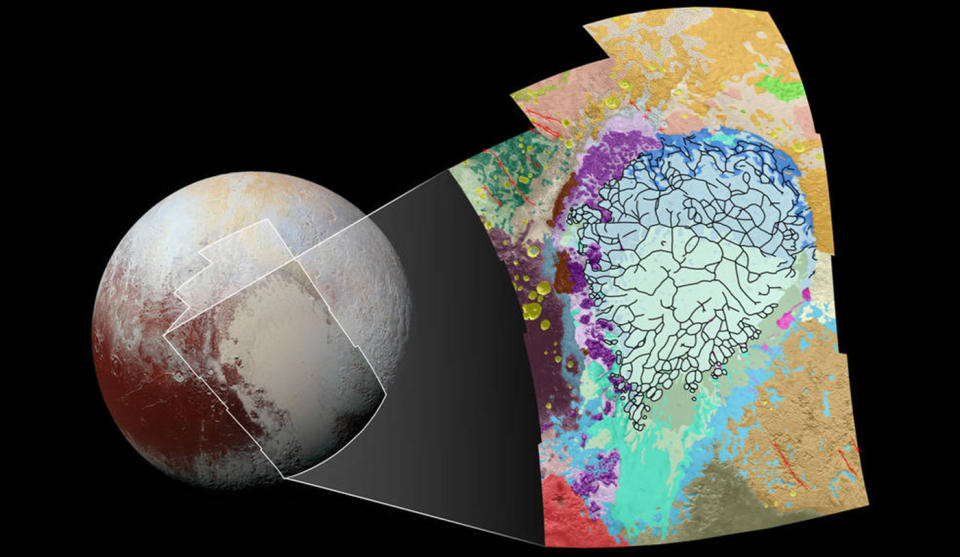

We used to think of Pluto as a remote frigid rock, but since the New Horizons visit, it's vying for the title of the solar system's most interesting (ex-) planet. An earlier study showed that its core is warm enough to support a liquid water ocean, and now we've learned that it might be huge -- at least 100 km (62 miles) deep. The evidence, according to the team from Brown University, comes from a likely impact with massive asteroid.

Pluto's most significant feature is the Sputnik Planam, a heart-shaped crater formed by an impact with an object up to 200 km (125 miles) across. Normally, such a crater would create a "negative mass anomaly," or a gouged-out hole with less heft than the terrain around it. However, "that's not what we see with Sputnik Planum," says Brown University geologist Brandon Johnson.

Instead, the region unexpectedly has more weight than scientists expect. They know that because of Charon, Pluto's moon. Like ours, it's tidally locked with Pluto and always shows the same face to the planet. Interestingly, the Sputnik Planum sits right on the tidal axis, suggesting that there's more mass in that area. "As Charon's gravity pulls on Pluto, it would pull proportionally more on areas of higher mass, which would tilt the planet until Sputnik Planum became aligned with the tidal axis," the paper states.

A closeup of the Sputnik Planum impact crater

So why would a crater area be so heavy? The researchers theorize that when a large body impacted Pluto, it created a trampoline effect, drawing material near the core toward the surface. If that material was liquid water, "it may have welled up following the Sputnik Planum impact, evening out the crater's mass," the paper says. Nitrogen ice later filled in the crater to give it extra weight, resulting in a positive mass anomaly.

For the simulation to be accurate, the liquid water below the surface must be at least 100km thick with 30 percent salinity. That might seem impossible on a planet with a surface temperature of 44K (-380 F). However, scientists think that radiation heating at the core of the planet and the 300km (200 mile) thick insulating ice shell makes liquid water feasible, in theory. "It's pretty amazing to me that you have this body so far out in the solar system that still may have liquid water," says Johnson.